Long before the coming of Christ, humanity’s quest for the Absolute gave rise in various religious traditions to expressions of monastic life. The many different forms of monastic and ascetical life throughout the centuries bear witness to the divine destiny of the human person and to the presence of the Spirit in the hearts of all who seek to know what is true and ultimately real. There is a “monastic” dimension in every human life which the monk witnesses and affirms, just as every Christian call witnesses to that dimension present interiorly in every other Christian.

In the early Church, ascetics and virgins followed the Spirit’s call to a more intense life of prayer. During the third and fourth centuries, with the exodus to the desert, Christian monasticism began to take on those forms of community life and solitude which would determine its later development. This tradition at its best always deeply esteemed marriage and single life in the world as ways to holiness in rich complementary to monasticism.

Saint Benedict (d. circa 550), as author of the Rule for Monks, has always been considered the Western Church’s lawgiver and master of monastic living. Saint Romuald (d. circa 1027) and his disciples (Camaldolese) also profess this rule.

The Rule of Saint Benedict is a synthesis of Christian spirituality including key elements of scripture and the fruit of the first centuries of monastic experience. Drawing on these directives, norms, and precepts found in the Gospel, the Rule wisely blends them with the historical and cultural context of its time. Thus the Rule of Saint Benedict unites the purity of timeless teachings and the characteristics of the author’s own holiness and prudence with spiritual and juridical elements that are linked to his time and so are subject to modification as they are reinterpreted for each age.

Saint Romuald lived and worked during the late tenth and early eleventh centuries. He fully realized in his own life the spirit of the Rule, and he wisely reinterpreted it, emphasizing the solitude of the hermitage. Saint Romuald wanted the hermitage to be characterized by a greater simplicity and a more intense penitential and contemplative practice. Therefore he freely adapted some juridicial and material structures of the cenobitic (communal) and anchoritic (hermit) life as they were lived before him, in order to respond to the spiritual needs of his contemporaries and to the “voice of the Holy Spirit, who presided over his conscience.” (from Life of Blessed Romuald by Saint Peter Damian, #53). The Camaldolese hermitage is a special fruit of Saint Romuald’s broad and varied monastic experience as a reformer and founder. The hermitage retains elements of cenobitic (communal) living, at the same time offering the possibility of greater solitude and freedom in the inner life.

The Camaldolese Congregation (of the Order of Saint Benedict) takes its name from the Holy Hermitage of Camaldoli, founded by Saint Romuald. Quite early on, in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the congregation was formed with the founding or aggregation of other hermitages and monasteries. Today those include, besides New Camaldoli and Incarnation Monastery, several ancient houses in Italy, and foundations in India, Brazil and Tanzania. There are Camaldolese nuns in the United States, Italy, France, India, Tanzania and Brazil. Our congregation looks to Saints Benedict and Romuald with filial devotion and regards our holy teachers’ doctrine and spirit as perennially valid. Today as in the past, the Holy Hermitage of Camaldoli (Italy) is considered to be the head and mother of the congregation. For each age the Rule of Saint Benedict is interpreted by the Camaldolese Constitutions and the entire Camaldolese tradition.

In both the hermitages and monasteries which characterize Camaldolese life, the monks attend to the contemplative life above all else, which is seeking and communing with God in a very deep way throughout one’s daily life by a sharing in the Paschal mystery of Christ.

New Camaldoli Hermitage, Big Sur, CA was founded from the Holy Hermitage of Camaldoli, Italy, in 1958. New Camaldoli’s daughter house, Incarnation Monastery, Berkeley, CA was founded in 1979. Incarnation Monastery is also the seat of the Saint Benedict Monastic Institute and serves as the house of studies for New Camaldoli.

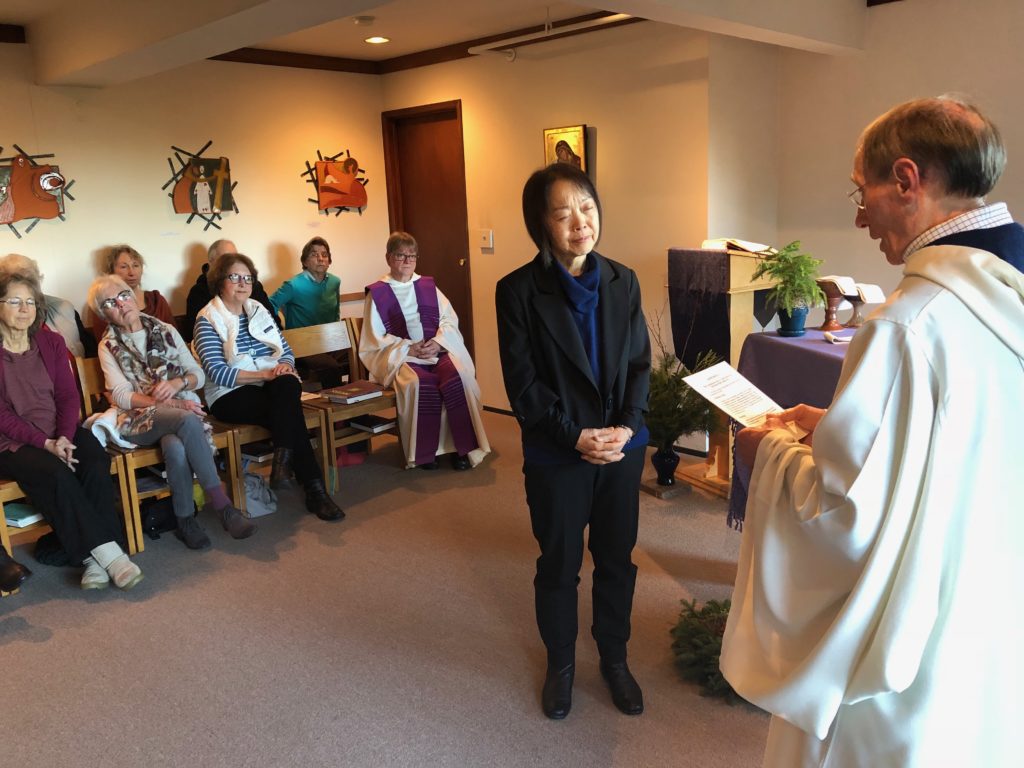

Camaldolese Benedictine Oblates are a group of Christians who experience an attraction of the Holy Spirit to deep prayer and experience a bond of friendship with our monastic community and its long spiritual tradition. In fact friendship is an important value cherished by the Camldolese family and therefore encouraged between monks and those living outside our houses. Oblates are extended members of the Camaldolese Benedictine family, seeking to share, in their own special way, in its way of living the Christian life. To this end, the Rule of Saint Benedict, the Camaldolese Constitutions and the rich and ancient Camaldolese tradition want to be adapted to the life of oblates living their own Christian vocation. For both monks and oblates, the heart of our life is the seeking of God, the following of Christ’s twofold command of love in the natural rhythms of daily life. Scripture, Liturgy of the Eucharist and the Hours, silence, solitude, deep interior prayer of quiet, work, shared life with others—these are the means which enable us to seek and find God with a pure heart. The oblate faces the challenge of setting up his/her own structure of life animated by key elements of the Camaldolese charism in order to live and grow in the life of Christ. Of course active participation in the local Christian community remains important for rootedness in the Christian life. Oblate spirituality seeks above all else a loving union with God through a full, prayerful life; a life which is at the same time both deeply interior and outwardly expansive in love and service of neighbor. It is a spirituality which is particularly nurtured through solitude and silence as well as through warm community.

The Rule for Oblates attempts to take the principal elements of the Camaldolese charism and apply them in general to the life of oblates without many of the structures of life here at the Hermitage. It is up to each oblate, according to the circumstances of their life, to set up their own structures for living the basic elements of Camaldolese spirituality, which are rooted simply in the Christian Gospel.